Alnylam is doing what the IRA is telling it to do

By Peter Kolchinsky, PhD & Tess Cameron

Peter Kolchinsky is a founder and Managing Partner at RA Capital Management and author of The Great American Drug Deal. Tess Cameron is a Principal in Strategic Finance at RA Capital.

October 31, 2022

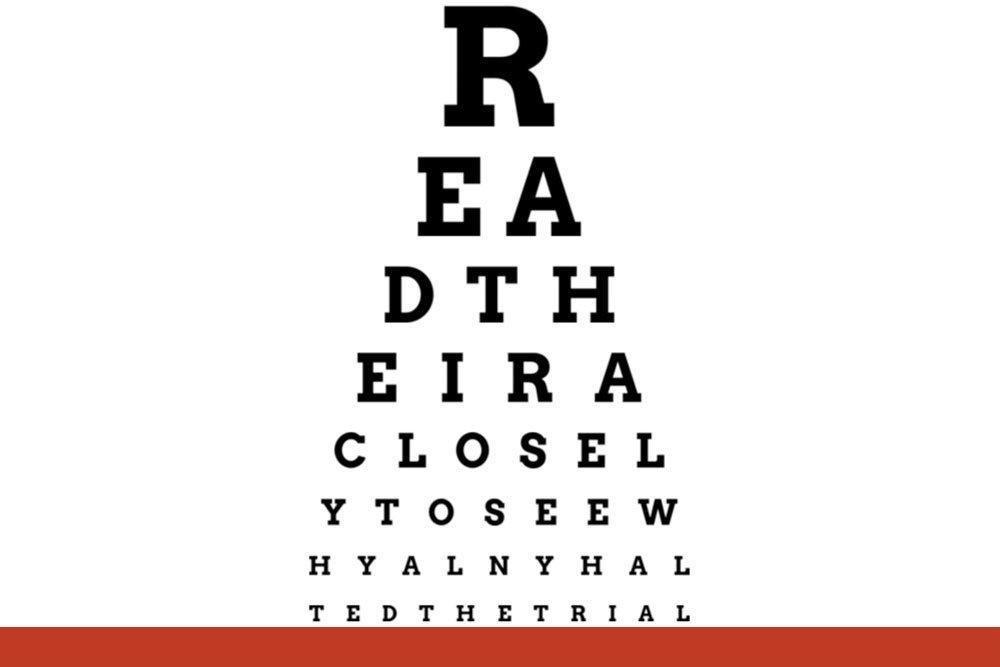

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals said last week that it was holding off on a planned Phase 3 pivotal study for vutrisiran in Stargardt disease (the drug is already marketed as Amvuttra in its sole approved indication so far, hATTR amyloidosis with polyneuropathy). The announcement illustrates how the Inflation Reduction Act is already having a negative impact on small molecule and orphan drug R&D prioritization, but nevertheless brought out skeptics of the biotech industry, who argue the new law is being scapegoated by innovators who want to overturn its Medicare drug-’negotiation’ provisions.

Alnylam said it wouldn’t start the study while it “evaluated the impact of the Inflation Reduction Act.” Might it start the study at some point anyway? Sure, maybe. But it probably shouldn’t, if it is going to act in an economically rational way to justify the hundreds of millions of dollars of shareholder money it spends on R&D. Sadly, the IRA gratuitously pits shareholders against the interests of Stargardt patients despite explicitly aligning shareholders with the interests of patients with ATTR amyloidosis, illustrating how the drafters failed to appreciate the negative implications of certain aspects of the law.

But the skeptics are suggesting that Alnylam is using the IRA as cover. That its decision not to test vutrisiran in that inherited form of blindness is because of something else. They are suggesting that vutrisiran won’t be the kind of big seller that Medicare would care about anyway. That it won’t even be a top 50 seller much less a top ten, and that IRA’s ‘negotiations’ won’t kick in for another 13 years, regardless. That after all, the IRA tells Medicare to take into consideration whether a company has recouped its R&D costs anyway. That there must be Some Other Reason, that we should tune out this nonsense when other companies say the same thing about their own drugs.

But these skeptics aren’t actually engaging with the law or the math it alters. The outcome of the IRA on innovation needn’t be a matter of opinion… it’s a matter of analysis. A four year old or Nobel laureate can make the case that 2+2=4 and they would be equally right. So don’t let critics distract you from the analysis by impugning the messengers. Hopefully we can start agreeing on the same set of facts.

Not a true ‘negotiation’

Let’s start with semantics. Since the law allows HHS to effectively tell the company what its Medicare/Medicaid price will be or pay an excise tax that increases to 1900% of the drug’s sales, it is price setting, not ‘negotiation’ (for more, see pages 35-42 here).

Single-orphans only

Amvuttra was approved in June 2022. It’s an siRNA, which means the IRA treats it like a small molecule, since it was approved via the NDA pathway. So under the IRA it would get nine years before Medicare’s price setting kicks in but only if it qualifies for and is selected for ‘negotiation’. (Were Amvuttra treated as a biologic, it would get 13 years before price setting kicks in.)

RA Capital has developed a variety of short, free, self-guided online learning modules called RA University. Our goal is to share practical and theoretical concepts fundamental to the biotech industry that aren't being presented anywhere else.

Technically it gets selected for ‘negotiation’ the first February after it’s been on the market for seven years (never get a drug approved in January/February if you can help it!) provided it’s got more than $200 million in Medicare revenue (we’ll come back to this), adjusted for inflation. So that’s February 2030, and then the set price kicks in two years later, in January 2032.

But Amvuttra is currently a single-orphan drug (its orphan drug designation covers ATTR amyloidosis). So provided it’s only on the market for ATTR amyloidosis, it gets an IRA exemption. That means that Medicare price setting won’t apply. The drug will be protected for the life of its patents.

So if Alnylam were to nullify Amvuttra’s single-orphan exemption status, it would go from what is commonly a 14-year period of patent-protected market pricing exclusivity to just nine years. Losing those five years means losing 35% of the protection period but over 50% of its revenues and well over 50% of its profits since it takes time for a drug’s revenue to ramp up. Why would any company willingly risk spending money on additional R&D for Stargardt disease if the reward for success is losing over half the reward for ATTR amyloidosis?

The brutal truth for Stargardt patients is that the new law straightforwardly disincentivizes a company from getting its orphan drug approved in an indication not covered by its original orphan drug designation. And if Alnylam pursued the Stargardt indication and the trial worked, that label expansion might hit around the end of 2026 – only five years before Medicare picks its price. Aside from losing the ATTR amyloidosis revenue, that’s not much time and much less possible revenue with which to justify the cost and risk of Stargardt development.

It’s unlikely another company would want to develop a separate anti-TTR RNAi for Stargardt, either. Because it would take so long from this point that if it worked, it would be launching close to when Amvuttra went generic (at which point insurers and doctors would just have patients use the older generic off-label). That’s generally why we rarely see trials for old drugs in new indications. So the IRA could be blocking Stargardt patients from knowing if an anti-TTR RNAi could work for them. Some day down the road, when Amvuttra is generic, Stargardt advocates could try to raise the funds to run the trial themselves, or ask the NIH to do it; yet neither approach has historically been a productive method for developing drugs. Unfortunately, this was the right moment for Alnylam to start a Stargardt trial and the IRA very strongly discouraged it.

Every drug, every year

Skeptics think that the IRA is focused on just a few blockbusters, or even just the top 50 blockbusters. What they seem to miss is that the IRA’s ability to whack drugs doesn’t stop after it’s knocked down all the big blockbusters currently dominating Medicare’s drug spending. It gets to whack as many as 20 drugs a year forever. Industry only launches 50 drugs a year and many of those are destined to be commercial disappointments without the IRA’s help. At steady state, the number of new drugs that generate so much as $200M of Medicare sales without a single-orphan exemption will be less than 20 per year, so CMS will have all the whacks it needs to knock them all down as much as it likes.

Play it out. In 2026, Medicare takes the ‘negotiation’ hammer to the first ten drugs it selects in Part D. In 2027, it selects 15 more Part D drugs. In 2028, 15 drugs in Parts B and D. In 2029 and thereafter, 20 drugs per year. By the time 2030 rolls around, it’s very likely all those one- and two-billion dollar line items have been whacked down by price setting. We’re probably getting close to the drugs that are just popping up over the $200 million threshold.

By 2032, we’re definitely there: fewer than 20 drugs reaching the minimum threshold and 20 slots open for ‘negotiation’. At steady state, each and every drug that is eligible for ‘negotiation’ will be ‘negotiated’, each and every year.

Will Amvuttra’s revenue come from Medicare? While the ATTR amyloidosis Amvuttra treats today affects a range of ages, its bigger amyloidosis indication, ATTR amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy, is roughly 70% Medicare. And that indication, which falls under the same orphan drug designation as polyneuropathy, should come on line in 2024. Analysts expect it to become a multi-billion dollar franchise for Alnylam.

And while Medicare is supposed to consider many factors when determining the ‘negotiated’ price, no one really knows what “consider” even means. Nor does a company have legal recourse if they disagree with HHS’ “considerations” (see page 41). Judging by how the government has misunderstood the consequences of the IRA’s wording, investors probably aren’t optimistic that the government will consider anything other than whatever justifies the lowest price they can set. After all, Congress is pressed to cut costs every year to make room for new expenditures, and the IRA will provide CMS with a way to cut as much as it wants from any drug deemed eligible for ‘negotiation’.

With no floor for how low CMS’s proposed price can go, and extremely punitive penalties for drugmakers that don’t accept CMS’s price, essentially, companies can’t say “no” and walk away.

And whether or not CMS decides a drug has recouped its R&D investment hardly matters.

A drug’s not supposed to simply recoup the R&D investment a company makes … it’s supposed to justify the risk taken to develop it. In retrospect, if the Stargardt trial worked, CMS would assume Stargardt was always definitely going to work. But prospectively, we can’t be sure. If it has a 25% chance of working, then it would need to generate more than 4x the actual cost of development to justify its development. That’s how the market works. But that’s not how the IRA is worded. It only mentions that CMS will consider the costs of development of that drug.

So we’re left with Alnylam acting rationally under the IRA. Other companies will have to do the same. And patients will be worse off for it. And yet, the IRA can be fixed: change nine to 13 and most of the IRA’s harmful effects on innovation will likely be reversed.

Please click here for important RA Capital disclosures.