Biotech’s Dulcius Ex Asperis: The Way Through This Downturn (Bionic Reading)

by Peter Kolchinsky, PhD

Peter Kolchinsky is a founder and Managing Partner at RA Capital Management and author of The Great American Drug Deal.

May 27, 2022

(To read this piece in its original, non-bionic format, please click here.)

The biotech sector is experiencing the most severe downturn of at least the last 20 years. There have been many other downturns in the more recent past, but they have not been as deep and they have been shorter. In some cases, they were decoupled from the broader economy. This one is different.

Here I discuss why the downturn may be so severe and protracted, the implications of valuations getting so low, how we as an industry can and must preserve the best of biotech’s R&D, and why biotech will rebound – plausibly sooner than other sectors.

The development-stage biotech industry will survive this downturn and eventually thrive again because of the biopharmaceutical ecosystem’s unique importance to solving some of the world’s greatest unmet needs.

But first, it will test the executives and boards that run biotech companies. Each has a fiduciary duty to one or more specific companies. Abundant access to capital in the recent past meant that all these companies were driving together along a broad highway with plenty of fuel. But the road has narrowed and threatens to narrow still, and there’s no longer enough fuel to propel all the R&D that inspired us over the past several years. We can and must now be deliberate about pulling over some programs to ensure that others progress.

Short of research being invalidated by data or obviated by better ideas, no vital R&D needs to be abandoned forever as a result of this downturn. But we must prioritize what’s most viable and important today and return for other programs later, when we have capital to support them. Doing nothing is a terrible option. A traffic jam will not inspire the rest of the world to come back to biotech, which would only mean more R&D will run out of fuel eventually.

As for jobs, our industry has long labored under conditions where dollar capital exceeded human capital. Having all qualified people in our industry focus on fewer, well-funded programs should accelerate their progress, allow us to show the world our successes sooner, and someday attract the capital necessary to fire up R&D programs we’ve steered to the side of the road, as well as whatever new ideas we come up with by then.

We should recognize that the true measure of the world’s appreciation of our ecosystem is not the valuations of our development-stage companies but instead the demand from patients and physicians for the products those efforts ultimately deliver. As you’ll see below, big biopharmaceutical companies are generating more in revenues than ever before and they must remain acquisitive of new drug candidates to replenish their pipelines ahead of patent expiries. So what we’re experiencing now in the biotech sector is not a fundamental failure to create or realize value but a working capital problem we can work through prudently.

This downturn is severe

As of this writing in mid-May, biotech is down about 60% from its high in February of 2021. But as Figure 1 shows, smaller companies have suffered far more on a median basis.

Figure 1: Biotech performance (XBI) by market capitalization since Feb 2021 peak through May 24th, 2022.

Biotech surged as the world awakened to what biomedical innovation could do to end COVID-19. Investors flocked to its many promising technologies, bidding up stocks, making it easier for companies to get the capital to fund the many ideas that inspire us. But then the world decided it wasn’t really all that interested in biotech and turned its attention elsewhere, a moment marked when the biotech sector peaked in February 2021. For the rest of 2021, biotech valuations fell to levels that marked a clear sector correction yet remained within historical norms. The broader market and the economy were still humming along. Inflation hadn’t yet kicked in as a major threat, Russia hadn’t yet invaded Ukraine. Nasdaq and S&P indices would continue their climbs through the end of 2021, and only then start their declines.

Biotech, caught in the broader market undertow, suffered a correction on the heels of a correction, sending the sector into less familiar, fearful territory. A few of us were around during the downturn following the genomics bubble, but that was over 20 years ago and isn’t in anyone’s muscle memory. The fact is, the vast majority of the people who make up the biotech sector today find the current market conditions unique.

Consider that among 477 loss-generating development-stage public biotech companies valued between $50M and $10B, 109 are trading below cash, which, as my colleague explained, hardly means they couldn’t drop further. Some may deserve to have their value propositions discounted to zero, but a sell-off of this breadth and severity reflects panic, which is never rational. Some companies are trading far below even their dissolution value (i.e., their recoverable cash were they to cease operations and wind down).

So how long might these dark times last? Figure 2 shows XBI-tracked S&P Biotech Select Industry Total Return Index performance stretching back to the genomics bubble, including the major downturns along the way. We colored the lines red during corrections and then shaded them yellow and ultimately green as the market climbed up sustainably to new levels. These charts offer the best way to think about how long past downturns have felt like downturns.

Figure 2: XBI-tracked S&P Biotech Select Industry Total Return Index from 1999 through 5/24/22, with major corrections broken out. Color of line shows a subjective assessment of the degree to which investors might have felt they were in a downturn (red) vs. coming out of a downturn (yellow) and finally out of the woods (green).

The nadir of each downturn is only evident in hindsight. Note how the ups and downs following the actual nadir make it seem like the correction continues. I point this out because it’s common for downturns to be measured either by looking at when a chart has hit its nadir or when it has regained its former highs. However, neither is relevant to what we all really want to know, which is “When will we stop feeling like the rug has been pulled out from under us?” It’s entirely possible that we have already passed the nadir of this downturn on May 12th. On the other hand, as long as biotech bounces along near the nadir, it can feel like it could turn right around and set a new low. We don’t need to see biotech actually regain its lost ground to feel like the worst is over. We just need to see stability and an upward trend. That’s why the charts in Figure 2 are useful; our collective sentiment about the sector tracks the changing of the lines from red to yellow to green. That can take a while past the nadir. So we’re still too early in our recovery from this current downturn… if we’re even in a recovery.

Why have valuations fallen so much?

For now, it feels like the broader investor community is largely staying away from biotech. Some days, investors sell what they own at seemingly any price. For what reason? Why is the world afraid to invest in biotech?

A big reason is that some investors are just afraid to own any equities. They worry that inflation will erode some companies’ profits. They worry that inflation-fighting interest rate hikes will abruptly slow the economy. They worry such a hard landing might even result in deflation, which can cause people to hold off from making purchases, which then can cause a persistent recession with downward spiraling profits. Higher interest rates also mean higher discount rates, which reduce the value of distant profits. With such risks, it’s hard to know what to invest in, but to them, biotech doesn’t come across as a safe bet (although below I’ll take the other side of that argument).

And on top of all that, biotech is just so technically complex. Investing legend Peter Lynch advised everyone to invest in a well-researched subset of “what you know.” That pretty much nixes biotech for the vast majority of investors, even professionals. It’s a wonder they ever stray from that advice, but it’s no surprise they remember to follow it whenever they grow risk-averse.

Few people understand how to interpret uncontrolled (or even controlled) oncology data or recognize when a disclosed side-effect might preclude FDA approval. Unfortunately some companies try to take advantage of generalists’ ignorance by writing press releases that bury the bottom line amidst all kinds of shaded phrasing, which erodes investors’ faith in our sector to the point where they struggle to believe the positive-sounding headlines that are actually positive. And then there’s the fact that biotech does actually mostly fail.

Success is rare - that’s always been the case. Only approximately 10% of all drugs that begin clinical trials end up getting to market, and only a fraction of those are commercial hits. Biotech’s failure rate isn’t the reason for this downturn, though people do seem to focus on the failures more these days, as if they justify investor disinterest in biotech. Any stretch of time would be demoralizing to someone focused on the failure rate of our sector.

Figure 3: The proverbial glass. Nearly empty, or 10% full?

Sometimes people revel in biotech’s successes, but sometimes they just aren’t receptive to the idea that the glass in Figure 3 is 10% full instead of mostly empty.

And yet, that’s exactly what biotech is: 10% full.

What biotech skeptics are missing is that the 10% that doesn’t fail goes on to upgrade human health for the rest of time. The 10% that doesn’t fail collectively generates branded drug revenues of over $700B and fuels $200B/year in R&D funding before it goes generic. The 10% that doesn’t fail supports pharma’s ability to refill its pipelines by acquiring biotech assets, recycling talent and capital throughout the ecosystem.

But when everyone is searching for a safe place to put their money, it seems most don’t give a glass that’s 10% full a second look.

Exactly why are low valuations a problem?

To many, this may seem like a question with too obvious an answer to merit discussion. But I think that there are enough misunderstandings of exactly how investor portfolios link all companies in our ecosystem together that it’s worth getting down to some first principles.

For starters, it’s worth mentioning that for a company with enough cash to do the R&D necessary to prove that it has a product of undeniable value, a falling stock price is an annoyance (that is, until you are in the ‘danger zone’ of trading below your dissolution value, as described below).

Well-capitalized companies, at worst, risk an acquirer coming in with an offer at a 100% or even 200% premium that the board feels compelled to accept, even though they may believe the fair value of their product is far greater. So maybe they miss out on generating a greater return for themselves and shareholders.

Could the board just turn down such an offer? Maybe, but if the premium is high enough, it’s hard. That’s because any board that turns down a rich acquisition offer can’t afford for the company to fail. If they were to fail after turning down a lucrative acquisition offer, they would face shareholder lawsuits. So boards find it safer to accept such offers. One might think that shareholders would object to a company being acquired at much less than its fair value. But say a stock you think is worth $50 is trading at $5 and an acquirer offers $15; odds are most other shareholders don’t think it’s worth $50. If they did, they would have been more aggressively buying the stock when it was at $5, bidding it up to $10 or $15 at least, so that an acquirer would have had to offer a price closer to $50, maybe $20-30, to successfully buy the company.

So that’s the primary consequence of a well-capitalized company’s valuation dropping during a downturn.

If a company has a relatively low burn rate relative to its market capitalization, then even if it will need to raise more capital, it knows that it will be asking its shareholders for only a little more investment relative to what they have at risk already. Even if they will need to offer a discount to get the cash they need, they have a high enough valuation that there is room to offer that discount. Current shareholders of that company won’t like the dilution, but again, it’s more of an annoyance than an existential threat.

The problem is when a company’s valuation drops to such a low point that the amount it will need to raise is a large amount relative to what investors already hold. A $1B market cap company burning $100M/year that wants to raise two years of cash is only asking its shareholders, who collectively own nearly $1B (whatever employees don’t own) to come up with 20% more to support their value proposition. But a $100M market cap company burning $100M/year would need to ask its shareholders to triple down.

When investors have enough cash to invest, they may come up with the money to fund both companies if their respective risk/reward propositions are compelling. If markets are strong and there are plenty of investors, then specialist investors might even prefer to focus on the smaller company’s recapitalization and let other investors finance the larger company, if they see enough demand that its financing won’t be done at much of a discount and therefore would represent a modest amount of dilution.

But what happens if new investors are largely staying away from the market, obliging biotech-dedicated specialists to make hard choices with their limited cash? Furthermore, what happens when investors are worried more about avoiding losses than generating gains and can’t take it for granted that the larger company will raise on modestly dilutive terms?

In aggregate, investors have more exposure to the larger company than the smaller one, though the opposite could be true for any one investor. As all biotech companies concentrate down to the portfolios of a smaller and smaller group of biotech specialists, each investor has to consider how it will keep its companies capitalized. Collectively, they have more exposure to larger companies than smaller ones and would want to conserve cash to preserve their more valuable holdings. Therefore, the smaller company might have a harder time raising as long as investors’ attention is focused on shoring up the companies to which they have more exposure. This is no different than how a large company with a shrinking budget will likely conserve its cash for its highest-value program, potentially defunding or slowing other projects.

In theory, a small company’s shrinking valuation is supposed to make it more attractive for investors, since the downside of failure is merely 100% but the upside of success grows higher as the stock price falls. The trouble with that theory is that it doesn’t take into account certain instabilities that occur the lower the price goes. One of them is the notion of a financing overhang.

Financing overhangs

Over the years, my team has explored whether there is such a thing as a financing overhang, a phenomenon whereby a stock supposedly performs poorly when a company clearly has to raise money because investors hesitate to buy, possibly figuring they can wait for a financing at a discount.

In our data, we didn’t see strong evidence for the existence of such an overhang. Consider that almost all biotech companies have to raise more money down the road, so if that scared off investors, there wouldn’t be a biotech sector, and all R&D would be done by big pharma, funded from the cash flows harvested from marketed drugs. But drug companies clearly are able to attract investors to fund them partway through development despite it being obvious that they will likely need to raise again. That’s because investors recognize that value is created along the way. They fear that if they wait until the next financing before investing, they won’t get to invest as much as they’d like in that financing since other investors will have the same idea. Along the way, some companies get acquired for a premium, rewarding those who held positions and leaving behind those who were waiting for a financing. So biotech investors have learned to invest despite the constant threat that companies will finance. It’s just factored into their risk/reward calculus.

We did notice that companies that were fundamentally failing at the R&D that defined them would struggle to raise money as their cash runway shortened. One could say they labored under a financing overhang, but I would argue that it wasn’t the need to raise capital that kept investors from wanting to buy their stock on the open market… it was just worsening fundamentals.

So under most conditions and for most companies, even those that are getting down to close to a year of cash and are likely to raise soon, I don’t believe that a “financing overhang” has been a real thing weighing on their stocks. I heard many people talk about it like it was real, but I didn’t see it in the data. One could find anecdotes supporting the concept, but one could also find anecdotes disproving it (e.g., stocks climbing as a company burned down its cash until it finally raised at a higher price than it was trading months earlier, ostensibly demonstrating that anyone who waited for the financing was wrong to wait).

However, the problem with our dataset is that, historically, there have been very few cases of companies trading down to levels where they had a very high burn-to-market cap ratio absent a clear R&D failure as the cause. But today, we have a fairly large number of companies burning more than their entire valuation, many of whom might feel like they haven’t really deviated from their R&D premise and have the same probability of success as before.

As of this writing, out of 477 development-stage public biotech companies, there are 52 whose annual burn exceeds their market cap, of which we estimate 22 will need to raise in 2022.

While such cases were rare in the past - typically idiosyncratic - we just experienced exactly the kinds of conditions that generate many such situations at the same time. When capital was abundant, we capitalized numerous ambitious companies with enough money to pursue big projects and explore novel modalities across many targets and indications. These companies, with investor encouragement, ramped up their spend to match their ambitions and capital. Instead of working with a small team on one project and spending $50M/year, they worked on multiple projects and spent $150M/year or even $250M/year. We all expect market conditions to fluctuate; few expect to end up in the worst biotech winter in 20 years. That’s okay – biotech companies shouldn’t run themselves to withstand every extreme situation. A downturn like this is not a risk for any one company to insure against on its own balance sheet or else every company would be overcapitalized the majority of the time. Everything we do is probabilistic. We just need to know that when winter comes, we can and will adapt as an ecosystem.

So as winter set in and nearly all biotech companies saw their valuations deflate, some came down to valuations even below their burn rates. Many companies have tightened up and cut their burn rates to keep their ratios down. Others haven’t yet or can’t without undermining their core R&D.

So many companies are now trading at such low valuations relative to their burn that we have to acknowledge that it’s quite possible that they are experiencing financing overhangs.

The lower a company’s valuation, the smaller the position that company represents in the portfolios of its shareholders, therefore the lower a priority it may be for them, and therefore the smaller the supportive “fan-base” the company may have when it seeks more funding. When the company’s burn rate is just too high relative to its valuation, making existing and new shareholders fear that it won’t be able to raise enough to pursue its core value proposition, investors might indeed hesitate to buy that stock and might even choose to sell it ahead of a financing, exacerbating the company’s situation. Some investors may come to see the value of selling such positions for the tax losses to offset gains elsewhere in their portfolio (the idea of gains in this market may seem silly, but investors may have long-held positions that they sell above their cost basis, creating taxable gains even if they are down for 2022).

This might feel like being caught in the gravity well of a black hole, but it’s actually not inescapable. Getting out requires either transformative data and/or a heroic transaction in which one or more investors invest enough cash in a company to make it clear that it’s going to weather the downturn, fixing whatever financing overhang might exist and diluting out any shareholders who might have preferred the company dissolve. So for the right R&D, on the right terms, and probably with a tightening of its expense rate, a company can get out of its spiral.

Falling further still — the danger zone

Those companies that can’t exit their spiral might cross down into valuation ranges that attract a different kind of shareholder: those seeking a return of cash, some of whom are willing to agitate actively to get it.

Every company has a dissolution value – the amount of cash that could be returned to shareholders simply by winding down, selling off whatever can be sold, and paying off liabilities. Under normal circumstances, it’s easy to assume this value is $0/share because we’re focused on the value of success. If a stock is trading at $20/share and investors are hoping that its trial works so that the company might be worth three times as much, it doesn’t much matter to investors whether there will be $0.20/share or $2/share of cash left over if the trial fails. To anyone holding that stock at $20 a share, both represent a near-total loss.

But to some investors, these details matter. Because if the company has $2/share in cash and is trading at $1/share, an investor could double their money if the company elected to distribute out its cash. It might seem counterintuitive that anyone could buy a company’s stock for such a low price. After all, why would any shareholder sell a stock below its dissolution value per share? Because most companies don’t elect to wind down and distribute out their excess cash. So some shareholders would rather take a tax loss and move on than sit around hoping management will do what management teams have rarely done: return cash to shareholders. And that presents an opportunity for investors that are willing to actively cajole management to cash out.

So in terms of what happens if a company’s valuation drops, drops, drops: it goes from being an annoyance, to creating a financing overhang, to entering a zone so low that management loses their mandate to even run the company. That’s the point when shareholders are so eager to get out that they are selling at a price that gives cash-focused activists the opportunity to step in and actively push for liquidation. The stock charts of hundreds of public biotechnology companies show them to be at various points along this progression, with the pain of each company reinforcing the risks for others because of how their fates interact within investor portfolios.

Hard choices for investors

Specialist investors with large portfolios have most of their exposure in highly valued companies. This doesn’t reflect a bias against small companies. It’s a consequence of the downturn. Even if an investor started with 20 equal positions in 20 companies all worth $500M, after this correction, some of those companies have dropped far more in value than others and become much smaller in the investor’s portfolio. That investor has much more to lose from the larger companies failing due to under-capitalization than from the now smaller companies failing. So cash and first principles constrain the investor’s strategy to focusing on the larger companies. They may want to fund the smaller companies. They may believe strongly in the value of the scientific progress those companies are capable of achieving. But when cash is tighter than before, investors must make hard choices as each company approaches its next financing.

Figure 4 shows that of the 477 loss-generating development-stage public biotech companies, 144 likely need to raise money before the end of 2022. Cumulatively, they will need about $15B just to fund themselves for one more year. This is going to be easier for some than for others.

Most financings are currently done at a notable discount, so the smallest companies need to raise almost their entire market caps just to fund themselves for one year. By comparison, the larger companies that no doubt represent a larger share of most investors’ portfolios will need to raise a comparatively modest fraction of their valuations to keep going. Before investors can hope to generate a gain, they must reduce their biggest risks of loss; that means prioritizing the preservation of their larger positions by being ready to fund them with their last remaining dollars, raising the bar considerably for smaller companies.

Figure 4. Amount of capital that development-stage biotech companies will need to raise in 2022, by market capitalization. Data from FactSet, RA Capital as of 5/24/22. Only shows biotech companies with market caps $50M - $10B and negative free cash flow (i.e., burn).

With the broader investment community shunning biotech, those funds that specialize in this space will shoulder the burden. They likely have little cash on hand and need to sell something to buy something. So if these 144 companies are going to disproportionately look to biotech specialists for $15B of funding (maybe more, since companies often try to raise more than one year of cash), many companies won’t get what they want; those that get what they need will count among the fortunate.

The markets are creating a forcing function whereby the limited supply of cash is making investors choose the companies that they believe stand the best chance of surviving this downturn … and also generating a return.

Small companies may offer the most upside, but their low valuations suggest that currently they have small fan-bases, though that can be misleading. As I discussed above, there may be a financing overhang phenomenon keeping a growing number of interested investors on the sidelines, in which case the company may be able to get more capital than the trajectory of its stock price would suggest. Usually CEOs have a sense whether investors are eagerly awaiting an opportunity to participate in a financing. In fact, now is exactly when large biotech specialists have the best opportunity to capitalize what they consider to be high-quality but grossly misunderstood small companies on very attractive terms. We’ve already seen and will no doubt see more of such financings.

So small companies who have their fans will get through this. But many others won’t. If investors aren’t knocking louder and louder on a company’s door as its stock drops lower and lower, that doesn’t bode well for its ability to finance. The end of a company is not the end of its people or the knowledge they generated; every biotech company that’s ever been continues onward in the work of its people elsewhere in our ecosystem (indeed, they are needed elsewhere on understaffed R&D) and can better the choices we make based on the lessons they leave behind (if we study them). Yet we can all empathize that it’s painful for anyone to consider that their company might not survive this downturn.

This isn’t just a problem for companies trading below cash right now or that are running low on cash. Even companies with longer cash runways or lower burn/market-cap ratios must recognize that their fortunes might change (Figure 5). Any R&D snag or sharp word from the Fed could cut a biotech company’s valuation just as it’s hoping to raise more money. And there will be hundreds more companies that will need to raise tens of billions more in 2023. Should this downturn continue into next year, the challenges they face may be as great or greater than those faced by companies raising now.

Figure 5. Data from FactSet, RA Capital as of 5/24/22. Only shows biotech companies with market caps $50M - $10B and negative free cash flow (i.e., burn).

I’m not suggesting that it’s likely that biotech will experience conditions that are this severe into next year. I think there is a good chance that the sector will rebound strongly from these levels and may have already begun its climb. But just because investors might generate returns into the end of 2022 and through 2023 doesn’t mean that companies shouldn’t plan for the possibility that the recovery won’t come in time for them. Investors might generate their returns from a spate of acquisitions, but that doesn’t mean that they will immediately finance all companies that need financing. Sector indices could surge by 30% from here and there would still be many struggling companies. So management teams and boards need to plan for that even as they hope for a speedy recovery.

The next right thing, quickly

Since the last major downturn was in 2015-2016, many current CEOs of small public companies have not been through a prior downturn. Many lack experience terminating R&D projects due to capital constraints or negotiating a financing down-round. This market offers a trial by fire. It’s going to require that experienced board members guide executive teams through scenario planning that involves considering some deep cuts to spending. Do these as soon as possible, not after cash has dwindled to the point that even deep cuts barely extend the runway.

There is ingrained skepticism as to whether executives, investors, and boards will really do “the right thing.” There is a perception that boards are complacent, preferring to continue to collect their payments rather than acknowledge that their companies are sinking under an increasing cost of capital. Even when a company shuts down its spending and ought to just return cash to shareholders, some think that VCs would sooner take another chance on some reverse merger candidate than to close out their positions and return a fraction of a dollar to their LPs.

But the majority of board members are interested in making those difficult business decisions and do not want to sit idly by as a small company shrinks further. Suggestions that they are motivated by self-interest do not hold water: their stock options are probably already far underwater, and their payments are typically modest compared to those from their day jobs. They have more to gain from doing the right thing than by living down to the world’s meager expectations and ruining their reputations.

I’ve likewise found most CEOs to be thoughtful and realistic about the capital environment and how their companies are positioned. If they seem resistant to doing “the next right thing,” it’s because they want to really understand what is the right thing. What’s obvious to some is not obvious to others and may be wrong upon objective analysis. Analysis can take time - most strategies evolve over the course of several board meeting cycles - but, in my experience, many boards are likely to be reacting to current market conditions with a greater sense of urgency, working closely with management on the scale of weeks to review scenarios and inform near-term decisions.

If presented with the opportunity to, for example, merge their company into another to achieve efficiencies, CEOs know that the world expects them to fight over who gets to be in charge. Most don’t want to reaffirm that stereotype. This market is exhausting and imposes a harsh reality on everyone. It’s a prisoner’s dilemma in which the punishment for failure to cooperate is that a CEO not only loses their job anyway but will be remembered as clinging to it to the detriment of the people they professed to serve.

Sure, there will be examples of this. But I think we’ll also see many people who run the scenario assessments, engage as a board, and make a thoughtful decision. It’s what their shareholders expect.

So let’s think through some of the options facing public and private boards under various circumstances.

We can preserve our most precious R&D by seeking efficiencies

Companies must think about how to do the most they can with the resources they have now; they might not have access to those resources in the future. That means boards and management teams throughout the ecosystem are scrubbing their pipelines to identify the best of their R&D programs. Everything else must be considered as potentially expensive ballast, to be jettisoned before the whole enterprise is dragged down into insolvency.

That means companies won’t start some planned trials and will halt trials already underway. For now, there are still plenty of biotech jobs, because many companies that do have a lot of cash were struggling to staff up. Ideally, people who lose their jobs working on a deprioritized project will find jobs working on R&D that passed a belt-tightening review and is presumably of greater value. If the R&D that continues is now more likely to succeed because it’s finally adequately staffed, then this market downturn might even have a silver lining (i.e., resolving the “inverted capital dilemma” that occurs when there is more money than people in a sector).

But this “silver lining” can be jarring and painful for people, who don’t see it like economists do. Companies should be open with their employees and let them know that they will have help searching for new positions and time to find one if their program ends up defunded.

Besides making cuts to spending, companies are entertaining previously unthinkable pharma partnership terms and acquisition prices. We haven’t yet seen many smaller, private companies merging with one another to achieve synergies to resist capitulating to these market conditions. Investors have already started looking for those in their portfolios as they see the total cash needs for their companies and look for ways to be more efficient. Starting up a new company might mean pivoting an existing one and applying its people and cash to a new, better idea.

I say all this as someone who loves the breadth of our industry’s R&D and appreciates the value of all we learn, even from our failures. I hate that conserving cash means we won’t be able to run some experiments, the results of which could guide us towards breakthroughs. And yet, the only way that society will entrust any of us with the capital to fund more R&D so we can chip away at disease and make our children’s lives better is if we are prudent, investing only in projects that exceed whatever cost of capital the markets dictate. Today, that cost of capital is very high, and therefore we must raise the bar on ourselves. We must park some R&D by the side of the narrowing road to ensure that other projects continue. Just as a large company would easily redirect capital among its divisions in response to a change in its R&D budget, so must we all work urgently to redirect capital among companies within our ecosystem.

Cash-rich shells should return cash unless investors eagerly support a reverse merger

These markets may force more public companies to capitulate entirely and become cash-rich shells. Some will look for private companies to merge with. These reverse mergers are nothing new; they typically happen when a public company concedes that its R&D didn’t pan out and shuts everything down, and most of the time the rest of the market is humming along just fine. But the market downturn is synchronizing the capitulation of many public companies whose R&D hasn’t so much failed as has been deprioritized due to capital constraints. The market favors some R&D projects over others, driving a shift of people and capital to the surviving programs. As an increasing number of cash-rich companies become shells and assume that they should start hunting for reverse merger candidates, they will discover that it’s a lot harder to pull off a successful reverse merger given current conditions.

That’s because shareholders of companies trading below their dissolution value can argue that they have more to gain from a simple dissolution or at least distribution of excess cash than diluting themselves with a reverse merger and spending the shell’s cash on a R&D that those shareholders didn’t select for themselves. So upon Shell X announcing that it intends to merge with Private Company Y (or really do anything with its cash except return it), it might face a shareholder revolt that attracts activists who vote down the merger, essentially forcing the company to distribute its cash to shareholders. Knowing this, all shells are limited only to targets and only on terms that investors find compelling.

How have so many reverse merger transactions succeeded in the past? A company only needs a majority of the votes that are cast, and most investors end up abstaining, so only a small number of “yes” votes seal the deal. But with cash scarce and activists already lining up their positions, I don’t think it’s going to be so easy for cash-rich shells to garner support for reverse mergers.

If a shell company is trading below its dissolution value and proposes a reverse merger, unless shareholders find that more compelling than dissolution and bid up the stock above the dissolution value, the reverse merger could very well be voted down in favor of pushing the company to distribute its cash back to shareholders (a process that can take many forms). So getting a majority of investors on board with a reverse merger is critical.

Can you imagine the management team of Shell X taking the management team of Target Y on a kind of test-the-waters roadshow in these markets to assess if enough investors like Y and the terms of the deal enough that, once it is announced, those investors are likely to race to buy Y’s shares so they can vote for the merger? Yes, this happens. This is how reverse mergers get done.

But now can you imagine 40 shells trying to do this at about the same time? Some will find good targets on good terms and get their mergers done. But many won’t. So it’s important for all such companies’ boards and management teams to recognize that reverse mergers are just one of several options. They could also distribute their excess cash as a dividend or a buyback (e.g., even using a Dutch Auction Self-Tender), take whatever remains private, or even just go dark, delisting to save on filing fees.

(For more analysis related to reverse mergers, alternatives with examples of companies that pursued those alternatives, and shareholder activism, see these slide decks from Torreya and SVB Leerink.)

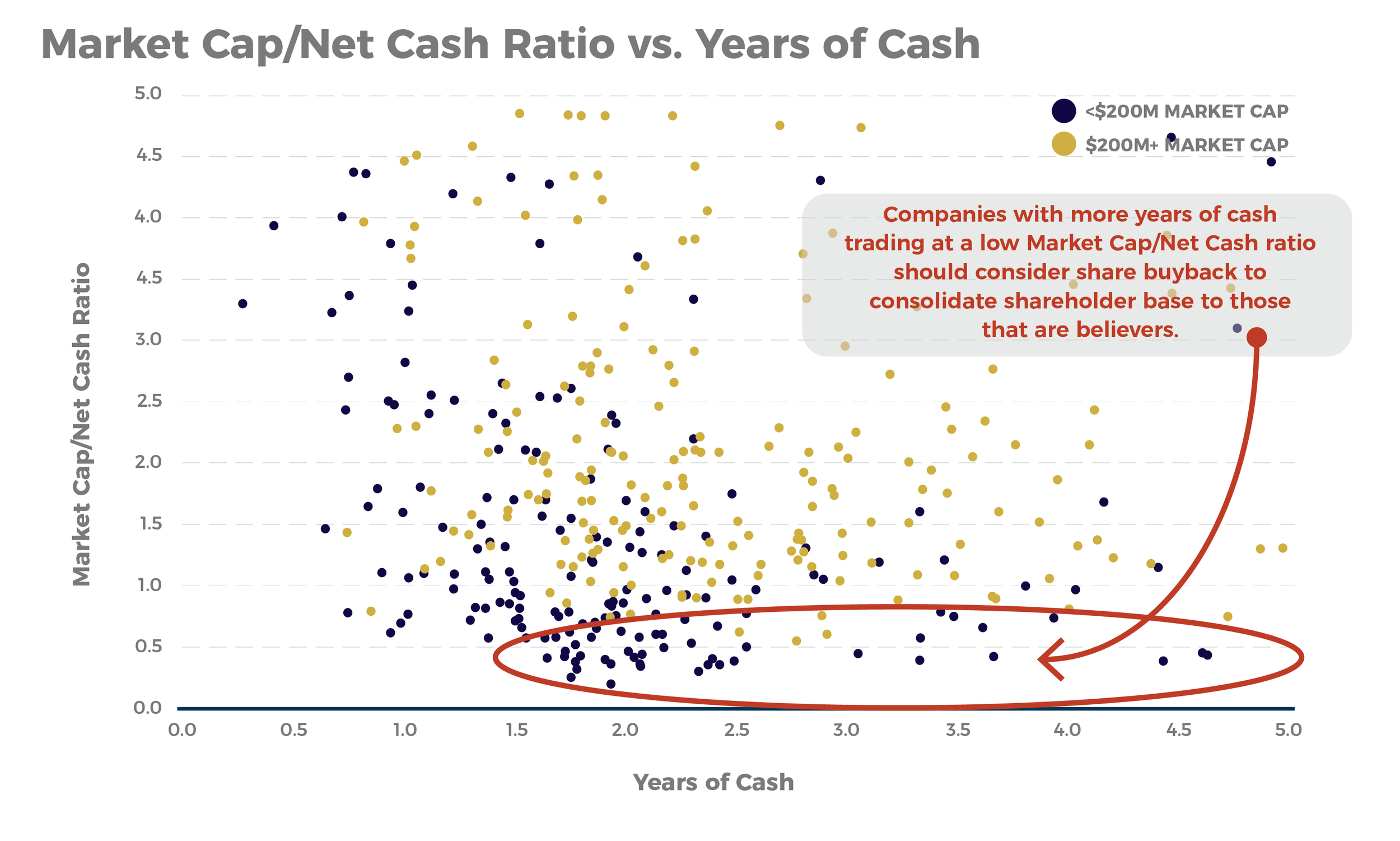

Companies in the the danger zone should consolidate down to their believers with a buyback

Some companies pursuing R&D they consider important and promising are trading in very dangerous territory, below their dissolution value. Activist investors could agitate to shut down their operations and distribute their cash. Boards and management can try to thwart activists, but as anyone who has gone through this can attest, it’s distracting, time consuming, and demoralizing.

There’s another way to ensure that a company in this situation continues to operate with a clear mandate from its shareholders: buy back stock from investors who want to tender their shares for a price that approximates the dissolution value (Figure 6). Buybacks can be executed quickly (within 40 days of the decision to do so) and are relatively inexpensive. The buyback gives disinterested investors the return and liquidity they would seek from dissolution and concentrates ownership of the company among the investors who don’t tender their shares because they believe in the potential of its R&D (think of it as reverse dilution).

Figure 6. Data from FactSet, RA Capital as of 5/24/22. Only shows biotech companies with market caps $50M - $10B and negative free cash flow (i.e., burn).

While reducing cash runway is always uncomfortable (it helps to pair the buyback with cutting burn), the fact is that nearly all companies will eventually need to raise more capital to reach profitability. So the buyback merely alters the risk/reward profile to be more favorable for those who value the R&D. If the R&D program goes well, the company will likely need to raise again, sooner than before (though that depends on the degree to which the company also cut its burn rate), but it might be able to do so at a higher price/share (one would hardly expect lower) than had it not done the buyback. That would leave the shareholders who didn’t tender their shares owning at least as much or more of the company than had the buyback not happened.

Management teams should always strive to operate with a mandate from the majority of their shareholders (stock trading above dissolution value is a useful biomarker), like a government operates with a mandate when a majority of voters support them. While lawyers can equip a board with the tools to retain control of a company for a while even as it continues to trade below its dissolution value and activists agitate, such tactics are akin to ruling by force.

Setting aside whether there is any honor in running a company without a mandate from a majority of shareholders, that’s also a uniquely risky road: a board and management team could come out looking heroic if the R&D works out and the stock trades up, but the downside of failure is magnified by Monday-morning quarterbacking from activists that argue the board passed up the chance to unlock shareholder value through dissolution. The lawsuits are unpleasant but likely not financially dangerous to executives or boards that can show they made carefully thought-out decisions. But that kind of failure sticks with executives and board members for their careers. It’s not a tradeoff they normally have to worry about when their stocks trade above dissolution value, but it’s one that many teams need to consider now.

Were executives and boards to resolve this tension by buying out the non-believers, they would operate with a mandate from their remaining shareholders (which means a majority, not necessarily all), who now also enjoy a greater stake in the upside. That’s so much better than continuing with business as usual as activists load up on the company’s stock preparing for a battle.

This is the kind of capital efficiency that would immediately benefit our ecosystem.

Need to finance? Just find a clearing price and raise

The public markets continue to fund R&D precisely because of the price discovery mechanism that finds clearing prices at which parties are willing to transact. In other words, the public markets are functioning. The problem with finding a price at which a company can raise the capital it needs tends to be on the private side of the market.

Private company valuations are subject to those same market forces but without real-time valuation readouts. That may give the false impression that a company’s valuation is unchanged from its last round. Some may even think that, since they have made meaningful progress, their valuation necessarily should be higher, as if the realities of the public side of the market don’t apply to them.

Unlike public financings, which are at least roughly guided by many recent transactions, private financings require that people express their valuation preferences to one another through conversations and in reference to highly subjective evidence (e.g., current or historic valuations of other companies, projections of profits, prior experience, etc.). In rising markets, the tendency for each round to be higher than the last typically makes these conversations easier. But in the context of a major market drawdown, valuation discussions become especially fraught. It’s been a long time since biotech has experienced such a deep and protracted downturn; our collective experience with these kinds of discussions is limited.

So let’s address the elephant in the room.

Sometimes, when executives, directors, or shareholders of a private company hear that an existing investor is unwilling to invest at a flat or stepped-up valuation, they can perceive that as disloyalty to the company or as somehow undermining the pursuit of the company’s great science. This exchange is unhealthy and stems from fundamentally misunderstanding what’s important.

Most specialist biotech investors are passionate about biomedical innovation and the pursuit of great science. At the same time, institutional investors must generate adequately high returns to be permitted by their Limited Partners (i.e., pension funds, university endowments, individuals, etc.) to continue to serve as conduits of society’s capital into life science R&D.

Therefore, being passionate about supporting biomedical innovation for the long run requires earning an attractive return (one that is competitive with returns that investors could earn elsewhere, in other sectors or with other managers). If Fund Manager X invests in good companies at high valuations while other managers are investing in comparably good companies at lower valuations, Fund Manager X will find themselves generating a lower return than other investors. X’s LPs may then shift their capital to other fund managers. Every decision to invest means a decision not to invest that capital elsewhere, a phenomenon known as opportunity cost. Therefore, X is obliged to seek valuations that minimize incurring high opportunity cost. And investing in a company at a high valuation when similar companies trade for less comes with a high opportunity cost.

The desire to be able to fund great science over the long run therefore requires that investors not lose their jobs by incurring high opportunity cost. Just as no employee should be shamed for not taking a low-paying job when higher-paying jobs are available, similarly no investor should be shamed for not investing at a high valuation when lower valuations are available.

The role of proper competition

A properly functioning market requires competition. In the case of financings, this means that investors who aren’t willing to invest at a given price risk losing out to investors who are. That’s why investors who would prefer to invest at a lower valuation may agree to invest at a higher valuation: they don’t want to miss out on the return that may exist from the valuation that is offered.

Every investor should formulate their own notion of what valuation would inspire them to invest. A proper market relies on every interested investor to originate conviction in the value of a company. This means that it’s inappropriate to blame one investor's decision not to invest at a given price for other investors not wanting to invest at that price. If not enough investors want to pay $X to adequately fund a company, why should anyone pay $X? They shouldn’t. And telling each investor that others are eager to invest at $X valuation to pressure them into investing at that valuation is a dangerous game that risks a company’s credibility if it’s not true (and even if it is true, risks building one’s shareholder base on borrowed conviction). Borrowed conviction leads to herd behavior which leaves a company vulnerable; when one investor sells, others follow, until the price drops to levels supported by the few investors able to anchor to their own conviction in the company’s value.

Besides competing with other investors for ownership of promising companies, investors in one company are also competing with other companies for employees, who also have a right to consider their financial return when deciding which science to work on. Therefore, even when one investor might be in a position to dictate the valuation of a financing (e.g., if no other investors want to invest), they are obliged to consider the ownership stakes of all employees. Employees who feel they have been treated unfairly can seek employment elsewhere. Even amidst this downturn, the current job market is tight, which means employees have bargaining power.

The science doesn’t care about valuation

Valuation is a preference, not a right (unless contractually defined). Valuation emerges from reconciling the preferences of all stakeholders. That process is called price discovery. This is the market’s primary function.

The science doesn’t care about valuation. In fact, if the science could speak for itself, it would say “I don’t care what valuation you all agree to as long as you keep working on me, so just figure it out.”

Some may think that a venture fund should be OK with investing in an IPO at a high price if it is investing its pro rata (or less). But many funds draw on new capital when investing in IPOs, not just the accounts of the LPs that already have exposure to that company. Therefore, fund managers have a fiduciary duty to LPs for whom the IPO is their initial investment in the company. Furthermore, launching a company into the public markets at a disingenuous valuation means that the stock will only be that much more likely to go down later. That harms employees whose option grants are based on an improper price discovery process. Later, as employees find themselves underwater, they may leave, which does imperil the science.

If newly public stocks perform poorly, the world will know that investors are engaging in improper price discovery. LPs will withdraw their capital from funds that buy into those overpriced IPOs. Without that capital, companies won’t be able to go public.

That’s pretty much where things stand now. Investors are wary of IPO valuations and need confidence that all prices reflect current market conditions. So if existing investors simply mark up an IPO and manage to execute it with the help of the minimally necessary number of unsophisticated investors who don’t realize that insiders are being disingenuous, odds are higher that this IPO will break deal price once speculators realize there is no real demand for the stock. Each IPO that breaks deal price therefore contributes to the world’s sense that biotech is a dysfunctional sector, keeping investors from coming back into biotech with confidence.

Therefore, for the public biotech market to find its footing and start its recovery, we need to work through the hangover of private company valuations as they seek to go public, so that private companies once again are priced at some discount to where they would trade publicly. That’s going to require a lot of difficult conversations, but the sooner those conversations happen, the better. Otherwise, investors will continue to stick to companies whose valuations reflect market realities (i.e., those past their IPO lockups), which means private companies will have fewer financing options.

Private companies that don’t want to accept the realities of the public markets are not obliged to IPO. One can hope for an M&A exit instead, but pharma acquirers can be even more fickle than the public markets. They can try to raise another private round. But investors in a private round typically seek to invest at a discount to where they think the company will eventually trade publicly, so it’s hard to escape the implications of a public market correction on private valuations. Some private companies will look at the proliferation of cash-rich public shells and think that a reverse merger is the way to go, but activists who see more upside in the shell distributing its cash are visibly standing guard and asking for the opportunity to decide where the cash goes.

So if a private company needs more cash to pursue its research, it needs to come to terms with the fact that either you get it from pharma partners or you get it from willing investors, and the key to either is to be open to figuring out the terms for getting a deal done.

As far as loyalty to advancing healthcare, anyone willing to invest in a company at any price to fund its R&D is supporting scientific progress. There is no requirement that an investor invest at a valuation other than what they believe will generate an adequate (competitive) return, just as there is no obligation for a board to raise money on terms they don’t find favorable. If investors offer money on terms that a board does not want to accept, it is the board making the judgment call not to fund the research. Not funding certain research may be a sound decision, but if anyone at a company is wondering who to hold accountable for a given project not being funded, they should take it up with whoever on the board vetoes a financing because they want a higher valuation.

That does not mean that the decision to not fund a particular research project at a particular valuation is a wrong one; again, everyone has to strive for a competitive return and that means focusing on the science that’s worth funding.

If investors, both existing and prospective, aren’t willing to fund a company even at a valuation of essentially zero, only then is it fair to say that the investors aren’t willing to fund the company. This is rarely the case. Usually, investors are willing to fund the company, and it’s just a matter of discovering the valuation at which the company gets the money it wants from enough investors. Finding a clearing price for a financing is not an abstract concept – public companies have the benefit of the market approximating that for them every day and private companies can execute a step-by-step price discovery process to get to the same answer (e.g. here’s a basic, systematic framework private companies can follow for a private financing or IPO).

The sun will come out

We appreciate why investors might be worried that the broader markets, including biotech, could be in for a protracted downturn and things could still get worse. We would urge them not to think about biotech in the same way they think about other technology sectors.

Healthcare is non-discretionary and therefore essentially deflation-proof. People don't generally put off medical treatments, at least not for long. And great medicines have pricing power earned by virtue of the fact that they are extremely valuable to patients and payers and often cut costs incurred elsewhere in healthcare, like hospital stays. So if one worries about inflation, essential medicines have more pricing power than most products and are likely to be among the goods whose prices are inflating.

Also note that markets have consistently appreciated the value of these drugs when they’re in the hands of a larger pharma, regardless of market turmoil.

Consider the value attributable to two diabetes/weight loss drugs from Lilly (tirzepatide) and Novo Nordisk (Wegovy). These drugs offer the most stunning degree of weight loss of any drugs ever developed. Novo’s Wegovy is off to a strong launch demonstrating that patients will inject themselves weekly and insurance will cover their treatment; Lilly’s tirzepatide recently posted Phase 3 data that clearly position the asset as a blockbuster-in-waiting. Lilly and Novo have each tacked on around $50B worth of valuation attributable to these drugs alone, their stocks climbing even as biotech has been falling. That’s based on faith in what’s to come, not today’s revenues, as evidenced by how much their Price-to-Earnings (PE) ratios have climbed from the low 20s into the 30s.

In the hands of smaller biotechs today, that same value recognition would be unlikely. But pharmas are not separate from small biotech companies. They may have different shareholders, but they are part of the same ecosystem. And a major way by which pharma’s success feeds into the returns of development-stage biotech is acquisitions.

Pharmas are always looking out for their own futures, spending tiny fractions of their massive balance sheets and cash flows to buy products that will replace revenues they know they will lose as their older products face generic and biosimilar competition. The more they grow, the more they need to acquire to grow. And as they look around today, they should see a remarkable arbitrage opportunity: the same great products with great data that would get credit in the hands of a pharma are on sale, in some cases trading near cash, when locked inside smaller biotech companies. Pharmas aren’t oblivious to the inefficiency, and biotech assets will not be so inexpensive forever.

Once we step back and see development-stage biotech as a feeder of successes into pharma’s pipelines, a metric emerges. How big is the development-stage biotech universe compared to the purchasing power of the big companies that are capable of acquiring them?

Figure 7 shows how many years of the free cash flows of the top 24 biopharmas it would take to acquire every single small- and mid-cap publicly traded biotech company valued between $50M and $10B for a 100% premium (data as of May 10). So this isn’t actually just development-stage biotech; some are generating revenues and some are even profitable. And even with that, it shows that the biotech farm team is trading at the lowest multiple of industry free cash flows that we've seen in a very long time (consider that 2016 was also a dark time and we’re below those levels).

Figure 7. Sources: Bloomberg, FactSet, RA Capital. This chart reflects two times the cumulative market cap of all development-stage biotech with valuations of $50M-$10B divided by the FCF of the top 24 strategics with the cash flows to be acquirers. 2022 reflected valuations on May 10th and exclude recent acquisitions Sierra Oncology and Biohaven. For 2023 and 2024, we kept the numerator the same as for 2022 but used consensus numbers for strategics, which reflect a slight decline in total FCF due to falling COVID-related sales.

One reason for the collapse of this acquisition multiple is the steep decline in valuations of biotech since its peak, described above. And pharma revenues and cash flows have also grown, partly due to COVID-19 product sales. Since analysts predict that COVID-19 revenues will moderate by 2023 and 2024, we extended Figure 5 to include FCF projections for those years, showing that the acquisition multiple over current prices only slightly increases.

The market values all public small-mid cap biotech companies in the $50M-$10B range at about ~$330B (including all private biotechs would increase this modestly, by about 10% to $360B). So acquiring just those would take about ~$660B, or 2.5x the top 24 pharmas’ FCF, which are now over $260B/year. Those same pharmas already have $222B cash on their balance sheets, and with $260B of 2022 estimated FCF would end 2022 with ~$480B on their balance sheets, so they don’t even need to dip into their future FCF to acquire anything they want.

Of course pharmas wouldn’t actually acquire all these smaller public companies. They don’t need to. They focus on the ones they think are best, the very assets the biotech ecosystem should be shoring up today. Historically, pharma has spent about $40-50B on acquisitions of small companies each year. But now pharma is even bigger and more profitable, with more cash on its balance sheets than ever before. Being bigger, pharma needs to continue to acquire to stay at its current size or grow. Drugs still go generic and spur pharma to continue to look for ways to replenish its revenues. So one might expect that total acquisitions will be at least what they were in the past (if not greater).

So think of biotech as an incubator of tomorrow’s medicines, a farm team whose best players are drafted into the big leagues while the rest continue to work on their game. And due to this downturn, biotech has shrunk to a very small farm team relative to the major league franchise it serves. That’s untenable.

The destiny of most successful biotech drug development programs is to be acquired by pharma. That’s not a bad thing – it’s the way our ecosystem is designed. Developing a drug is one thing and figuring out how to commercialize it is another. Pharma specializes in commercialization and can do late-stage development well. By comparison, small biotech companies are quick and nimble at earlier-stage R&D. Small companies can also do late-stage development and, in rare cases, can do a good job of commercialization their own drugs, but game theory would argue that every member of the biomedical ecosystem should play to their strengths, so even companies successfully commercializing their own drugs can end up acquired by pharma, releasing R&D teams to focus on R&D again. Investors who receive a payout from those acquisitions recycle their capital into other development-stage biotech companies.

$50B of acquisitions at a roughly 100% premium generates about $25B of gains for the biotech ecosystem, which is 7.6%. And that’s in addition to the gains from some companies escaping the development-stage pool to become standalone profitable successes, like Vertex, Incyte, Moderna, and BioNTech, which development-stage investors could sell for a profit.

When biotech’s total valuation was larger (in say, 2020), $50B of acquisitions would have contributed a significantly smaller return. One would have needed to count on either pharmas acquiring far more than usual or on more biotechs achieving escape velocity. The latter isn’t impossible but would have required “this-time-is-different” thinking. Indeed, at the time, it did feel that way. Maybe COVID had awoken the world to the value of innovation and we would have the funding to work through tough science to create more breakthrough drugs like Trikafta, PD-1s, inclisiran (PCSK9), or tirzepatide for the many remaining unmet needs.

Not now. Valuations have shrunk considerably and it’s clear in hindsight that 2020 was just another swell, a passing wave like many past rallies swollen further by the moon tide of COVID and transient generalist interest. So be it. That kind of largesse has in the past funded a breadth of biotech R&D that laid the groundwork for sustained value creation later, ranging from Hepatitis C cures to immuno-oncology treatments to gene therapies. Vertex’s transformative cystic fibrosis drug Trikafta was based on research nurtured with cash Vertex raised during the genomics bubble.

And so the sun will come out. Meanwhile, we seek efficiencies and reset valuations for leaner times to find the clearing prices that keep R&D funded. We strive to move the biotech industry’s brilliance – its people and its energy and its singular purpose – to those most important and valuable opportunities. And we remind ourselves of the central importance of biotechnology innovation to the health of the globe and the health of our families. The health of all of us.

Further Reading

Please click here for important RA Capital disclosures.