Showing the math: How IRA destroys NPV

Showing the math: How IRA destroys NPV

Understanding how investors use NPV to value drugs at various stages of drug development explains what CBO's and other analyses miss.

Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash

Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash

April 3, 2025

The IRA makes most early-stage, small molecule drug development projects for diseases of aging uninvestable. We’ve been saying so for a long time, but if you’ve remained unconvinced, this new analysis may help you see the light.

But let’s take a step back. Since long before the Inflation Reduction Act was passed, investors and innovators have been warning about the consequences of slapping price controls on novel medicines. Before the IRA there was BBB. Before BBB there was HR-3. All of these proposed policies had a few things in common: they misdiagnosed the reasons people couldn’t afford medicines their doctors prescribe; they offered up price controls as the solution; they relied on faulty or “naive” assumptions about how investors make decisions; and they ignored the fallout for innovation.

And why listen to self-serving investors or drug companies when you can find someone to tell you price controls “aren’t a big deal” or that “industry can absorb them?” When told that price controls on novel medicines remove incentives for investing in the next generation of medicines, IRA proponents have pointed to existing empirical analyses and policy simulations that say otherwise – or said “well sure, but only a few drugs over a very long time, and those drugs probably were just going to be me-too medicines anyway.” They point to these analyses, which relied on incomplete aggregate data and/or simplified assumptions, and say that biopharma investors are crying wolf.

But these analyses do not reflect the reality of how investors make decisions about whether to fund a drug development program. One key analysis often cited by IRA proponents comes from the Congressional Budget Office, which forecast only a very slight decrease in the number of new medicines making it to market over the coming decades. The CBO had to make simplifying assumptions due to data and methods constraints. Yet, these estimates could have devastating real-world consequences on innovation, and more importantly, patients and their loved ones that are suffering.

Last year, a group of innovators, investors, economists, and advocates representing more than $332 billion in assets under management and 665 drug programs in development signed on to a letter asking the CBO to amend and improve its model. We wanted to help the CBO better understand how new drug funding and innovation decisions are made. In addition to telling them, we needed to show them.

Which brings us back to the new peer-reviewed paper published last week in Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science (TIRS), written by my colleagues Tess Cameron, Peter Kolchinsky, and me.

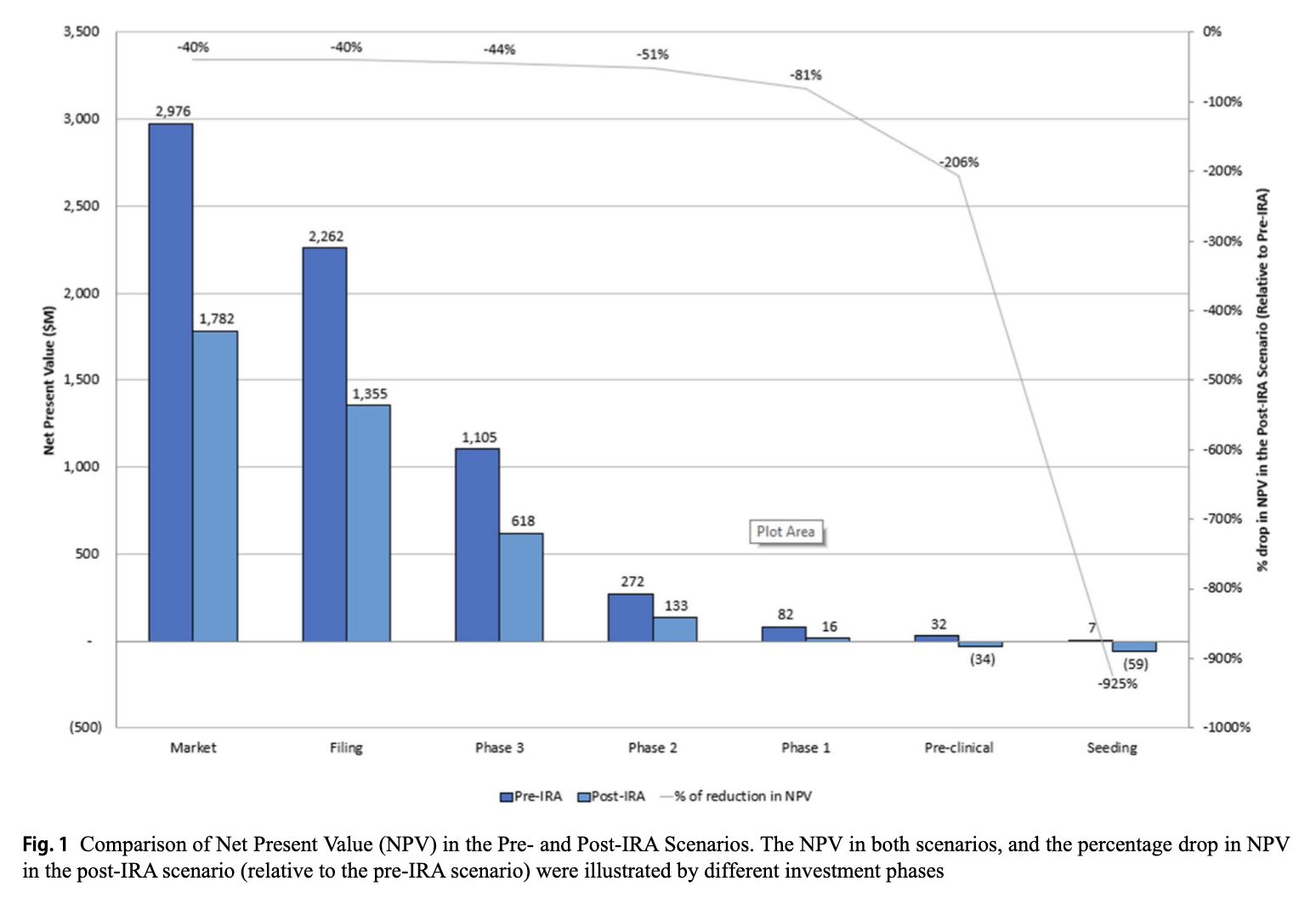

We conducted a project-level net present value (NPV) analysis using an illustrative case example modeled after the real-world launch curve of Entresto, a heart failure drug selected last year by CMS for the first round of IRA drug-price “negotiations.” We explicitly incorporated four key decision factors in the NPV model to illustrate the potential real-world impacts of IRA including:

- using discounted expected profits from US and ex-US regions to measure return,

- adjustments that investors made amid policy uncertainties in NPV modeling for potential projects,

- the impact of dilution of ownership due to the need of the company to raise additional capital at each stage of development, and

- the rate of return required by investors to allocate funds to potential investment opportunities.

By using realistic assumptions and inputs consistent with a real-world investment decision making process, we demonstrate how the IRA could decrease a project's NPV by as much as 40% at launch, and much more at earlier stages (illustrated by the Figure below). The NPV estimates indicate that, in the post-IRA world, this project would have been discontinued if investors were deliberating whether to advance the project into preclinical development or into Phase 1.

Our findings underline what we’ve been saying going back to HR3: investors will pivot away from small-molecule drugs for diseases of aging, preferring biologics or focusing on drugs treating conditions with extremely high unmet needs that are exempt from the IRA’s 9-year pill penalty. Net: the so-called “pill penalty” takes potentially better future medicines off the table for the patients who need them.

Drug development takes a long time. But it won’t be long before we begin seeing the consequences of the IRA’s treatment of small molecule drugs. It is disheartening to imagine a world where we are not funding development for more effective treatments or even cures for Alzheimer’s disease, or cancer, or any number of diseases that mainly impact older Americans. We hope our work helps improve the models that policymakers rely on when they evaluate impacts of laws like the IRA – and whether and how to tweak them once they take effect.

Oh, in case you are curious, our model is fully accessible and open-source in the supplementary materials at TIRS. Feel free to play around with it.

Related Reading

Photo by Toa Heftiba on Unsplash

Photo by Toa Heftiba on Unsplash

About the Authors: