Investors and academics: making beautiful music together

By Nadim Shohdy

Nadim Shohdy is an EIR at RA Capital and has over a decade of experience in commercializing drug discovery across diverse indications and modalities. Prior to joining RA, Nadim was at NYU School of Medicine as Associate Dean of Therapeutics Alliances, a drug discovery accelerator that de-risks academic research for partnerships with biopharma, investors, and nonprofits.

July 28, 2021

“VCs? Don’t get me started. They think everything is too early and expect us academics to crank out drugs! Most of the time you never hear back from them anyway.”

“This PI has interesting results but it’s too early for primetime. How can we invest when there are not even good data to demonstrate that the pathway is relevant in humans?”

Such frustrations are regularly echoed by academics and early-stage life science investors. Yet, despite the angst, both parties need each other to launch new and exciting ventures. The role of academic biomedical research as a major spark of innovation is well-documented from the birth of the biotechnology sector 40 years ago.

Stakeholders on both sides of the aisle have long opined on how to improve academic-investor interactions, an issue both multi-faceted and highly dependent on the specifics involved. My perspective has been shaped by living in both worlds, and is based on years of advancing drug discovery at the interface between academia, nonprofits, pharma, startups, and investors. I have been involved, directly and indirectly, on the science and business ends of dozens of diverse academic projects, some successfully partnered, others not. Indeed, success and failure alike have provided many valuable lessons on navigating this space. Last year, I joined RA Capital to focus on early-stage activities such as our RAVen incubator, supporting our portfolio companies, and helping evaluate startups for investment.

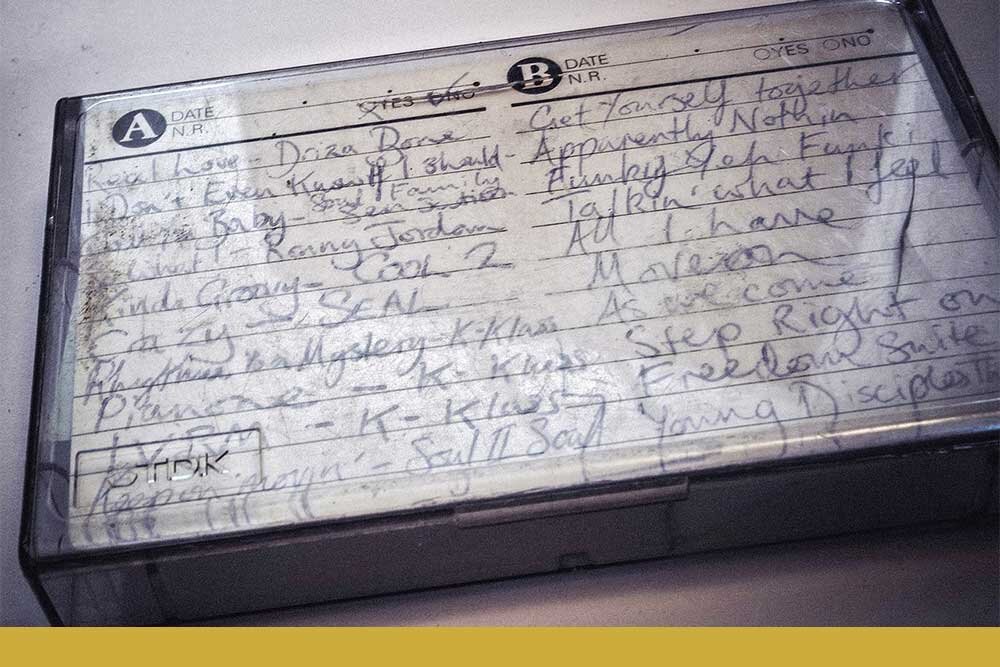

While every academic startup has its unique mix of salient details (science, feasibility, team, resources, clinical path, IP, commercial, even personalities and a little luck), several shared and interconnected themes rise to the top that may be useful to consider while listening to thematic (and eclectic) tracks.

"The Long and Winding Road"

To state the obvious, biopharma is extremely complex, but for our purposes let’s deconstruct it in an admittedly uber-simplistic way:

Developing a product is a long, unpredictable, expensive, multi-step path to the market.

Any startup that has successfully completed a step - preclinical or clinical - can still fail in the subsequent step, resulting (most of the time) in “Game Over.”

The earlier you start in the process, the greater the chance of crashing and burning before you get to commercial success.

Academic research is as early as it gets, and hence holds the highest risk of failure.

So why would any investor want to invest in academic startups?

Well, many therapeutics, platform technologies, and research tools offer clear examples of academic discoveries translated into commercially successful and societally important products. Moreover, as value is inversely proportional to risk, one can invest in more early-stage projects for far less than later-stage assets and realize far greater returns on the few that succeed.

"I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For"

Despite tons of publications, only a fraction of academic research will make it into startups; much less will achieve commercial success. And then there’s the elephant in the room: Data reproducibility is a well-known concern echoed by government, academia, and industry alike. Even with pristine data, biotechnology is generally unpredictable, so we can all agree that a startup founded on weak data is doomed. Problems with data reproducibility can be driven by a host of things such as limitations of experimental models, incomplete methods documentation, strapped resources, poor statistics, low-quality reagents and, in some unfortunate cases, outright fraud.

Again, despite the sobering reality, this vibrant, fertile soil has yielded too many advances to count, such as immuno-oncology, CRISPR, gene therapy, new vaccines, and protein degraders.

"Time After Time"

Investors are constantly analyzing ideas from faculty, technology transfer offices (TTOs), or newly minted academic startups. Due to scientific and clinical complexity, significant time is required for proper review. For many early-stage VCs, a time commitment can be more costly than a financial commitment, especially if we must roll up our “operational sleeves” to help build the startup to get it closer to success.

Okay, so let’s get constructive.

Selling an academic story to VCs boils down to clearly justifying the unmet need, generating a data package that supports the story’s potential, and effectively engaging investors. Intellectual property, management team, development plans, etc., are also important, but the former tend to carry more weight for very early spinouts. In a nutshell, investors will only come on board if they commit time to seriously evaluate the technology, see compelling data, and buy into the rationale to justify moving forward.

"You Can’t Always Get What You Want" (But You Get What You Need)

Articulating the problem a technology solves and how it accomplishes this is vital. As university research is mostly not applied, this requires reflection, getting out of the comfort zone, and pressure-testing by others.

Investors often encounter ideas in search of an application. Other times the application is obscure or not compelling. Claiming your work can lead to “a cancer drug” is too broad. Which cancer subset? Are there predictive biomarkers? How could it stack up against standard of care or other drugs in the same space? Similarly, a new platform manufacturing technology requires explaining where the specific need is compared to whatever else is currently used, and that this new process is feasible and cost-effective.

Nevertheless, investors sometimes can be the ones who are wrong about their assessment. We recognize this and see our failings in every technology that succeeds that we didn’t appreciate earlier on. We struggle with uncertainty, like everyone. So we try to keep an open mind and try to learn from when we passed on a great story.

Yet here’s where it can be especially problematic: Occasionally we have to say “no” even when we believe a project will likely succeed. We may love an idea and recognize that a product would help patients, but sometimes society doesn’t reward such innovation - as in the case of some antibiotics. In these cases, we’re forced to be the seemingly heartless messengers that “there’s not enough reward to do this,” which is especially painful when you are talking to a clinician who actually knows the patients who won’t be helped.

That doesn’t mean we accept the status quo. Investors - including my colleagues at RA Capital - are involved in efforts to achieve healthcare reforms that will hopefully avert price controls and open up previously unrewarding market opportunities so that we can say “yes” to more projects. (Check out this explainer from No Patient Left Behind that not only teaches how investors decide what to invest in, but also how price controls interfere with that process.)

"How Will I Know?": Aiming for a Compelling Data Package

Investors crave data to support taking the plunge. It’s not simply a need for “more data,” rather data to provide confidence that a new, unproven technology is reasonably understood, probably relevant to human disease, should be relatively safe, may be better than whatever else is out there, and is likely feasible to develop. Is this too much to ask for? Frankly, no, given the scale of investment, effort, and risk to build and carry a startup.

Nevertheless, academic stories need at least evidence of potential in these areas, not always definitive proof. It is understood that academics have limited resources to fully develop a technology, and that applied research is best conducted by the private sector. We accept risk, but can act on academic data, even with gaps, if those data are reliable enough to answer questions germane to building startups with firm foundations. Here are some tidbits that can collectively strengthen a story’s prospects:

Data from sufficiently powered, controlled, solid experiments addressing points above showing clear, statistically significant results is pure gold. Nothing dampens interest like n=1 experiments, phenotypes attributable to irrelevant mechanisms, use of poor quality and unreliable reagents, etc.

Unless the goal is the research tool or rodent market, data supporting translational relevance in human disease are essential. Biochemical, cellular, and mouse models are important for understanding underlying mechanisms, but data from human biospecimens or human genetics are critical. Biospecimen cores, patient-derived cell lines, humanized mouse models, and genetic databases are examples of resources to use.

Leveraging independent, complementary approaches to validate the story mitigates the unknowns of biology and experimental limitations. Don’t rely solely on your favorite assay, cell line, animal model, etc. Third-party data by contract research, collaborators, or even competitors can also provide such “belts and suspenders” data.

Openly recognizing the gaps in your data is crucial. Yes, you heard me right - being upfront about weaknesses is a good thing. Claiming your data are perfect will be met with suspicion, but an objective assessment of strengths and weaknesses is a breath of fresh air. Presenting the gaps also saves investors time in diligence and planning next steps to de-risk and advance the technology.

These points are analogous to criteria in grant applications or manuscripts, albeit with a more translational/applied bent. Sounds reasonable, right? Shouldn’t development of a technology aimed at helping patients also be founded on robust data?

"The Rainbow Connection" (with Investors)

While useful, a polished deck or snappy elevator pitch is not always critical for “hooking” investors. We can (and do) get excited by journal articles, conference presentations, or Zoom chats. Regardless of the first approach, the trick is to convey the points above to make the initial connection succeed and lead to more iterative back and forth to reach a decision.

Regardless of outcome, this is also a mutual trust-building exercise, especially with TTOs who regularly engage investors on promising innovations. Sending one or two top projects at a time is optimal, while sending a massive spreadsheet of all the “technologies available for license” is not. Sending investors projects claiming game-changing potential is wonderful, but if after five minutes of data review the conclusion is that the work is a proverbial “dud”, then trust is eroded for future interactions.

In turn, investors should carefully review (not just skim) whatever they agreed to review and provide appropriately detailed, constructive, and timely feedback. Radio silence or sending a short, generic “This is too early” reply is discourteous and wholly counter-productive in building relationships with academia.

Further, giving relevant, constructive feedback is more than simply a courtesy, it can directly lead to a project going from interesting to red hot when it helps principal investigators (PIs) generate data that plug up key gaps in the story. The investor who initially took the time and energy to get into the weeds with the researcher, highlight the gaps and even propose experiments, will have strengthened the relationship with the founders to better serve the resulting startup.

Let’s say we receive a pitch from a PI about a mAb they generated targeting a novel IO target that successfully flat-lined a mouse tumor. Although a promising start, an associate on our team who knows the literature may advise that mAbs against other IO targets have done the same (in the same model) yet failed in the clinic. In this scenario, we would need a rationale and data from the PI explaining why this particular approach would be expected to work. Further, we may even outline certain in vitro and in vivo studies to generate data supporting differentiation (and superiority) of his approach, providing us with the justification to advance to the next stage of diligence and maybe form a company.

Another scenario may include a PI with a recent paper describing a novel pathway in a rare disease. She has significant data from human genetics, knockout mice and cellular assays, with a working hypothesis that inhibition of a rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway may ameliorate disease. Although no chemical matter has been generated, our team recognizes the indication has a clear unmet need and a startup may be highly compelling from a commercial standpoint. However, the PI has not yet discovered which isoform of the target is involved in disease, a very important issue as our diligence reveals that one isoform is essential for homeostasis. We assess this is too early without more clarity on how to develop an inhibitor selective for the disease-relevant isoform.

A year later we check-in with her to find out she has identified the isoform and developed a screening assay. It’s possible that the new data still precludes us from a Series A financing, but our interest level now has increased. Now we might use our incubator to fund work at CROs and identify tractable hit compounds, leading to company creation with a seed-stage investment. And off to the races we go!

"It Takes Two to Tango"

Again, every story has its unique idiosyncrasies and requires effort to assess each opportunity in light of the challenges described above. For an academic, building an early-stage project and shopping it around to investors that are perceived as finicky and risk-averse can be daunting. Investors and academics alike need an open mind, an understanding of how the other operates, and more patience and humility.

Ultimately, this will reduce frustrations, manage expectations, build relationships, and help us navigate the applications of new biology together. We are in exciting times when investors are building early-stage incubators and teams to better engage riskier academic innovations, and many institutions have programs to better support faculty and TTOs in developing technologies and ideas. Such efforts will bring these two worlds closer, lead to fruitful startups, and energize investors more to engage with academia and keep returning again and again for an encore.